Young kids, 3-5 years old or so, love to run as fast as they can. They’re beginning to master how to walk or already have and given the chance, they will take off sprinting. Remember getting new shoes and seeing how fast they were?! It’s the shoes … it’s gotta be the shoes.

Moving into primary or elementary school, the movement bug is still there. Invasion games like tag are a lot of fun or even just challenging a friend to a race to see who’s the fastest. As for the latter, I recall a baseball trip to the Dominican Republic where I witnessed a group of 5 boys just challenging each other to races. It was just pure, organic speed training.

There is little doubt that sprinting speed starts to become an important and coveted physical attribute in youth sports during childhood and adolescence. And related to this notion is the interest in training sprinting speed in youth.

Age-related changes in sprinting performance

As we always should – let’s “first understand the system” (see The Roots of Growth and Maturation) of the normal growth and maturation or natural development of linear sprinting speed.

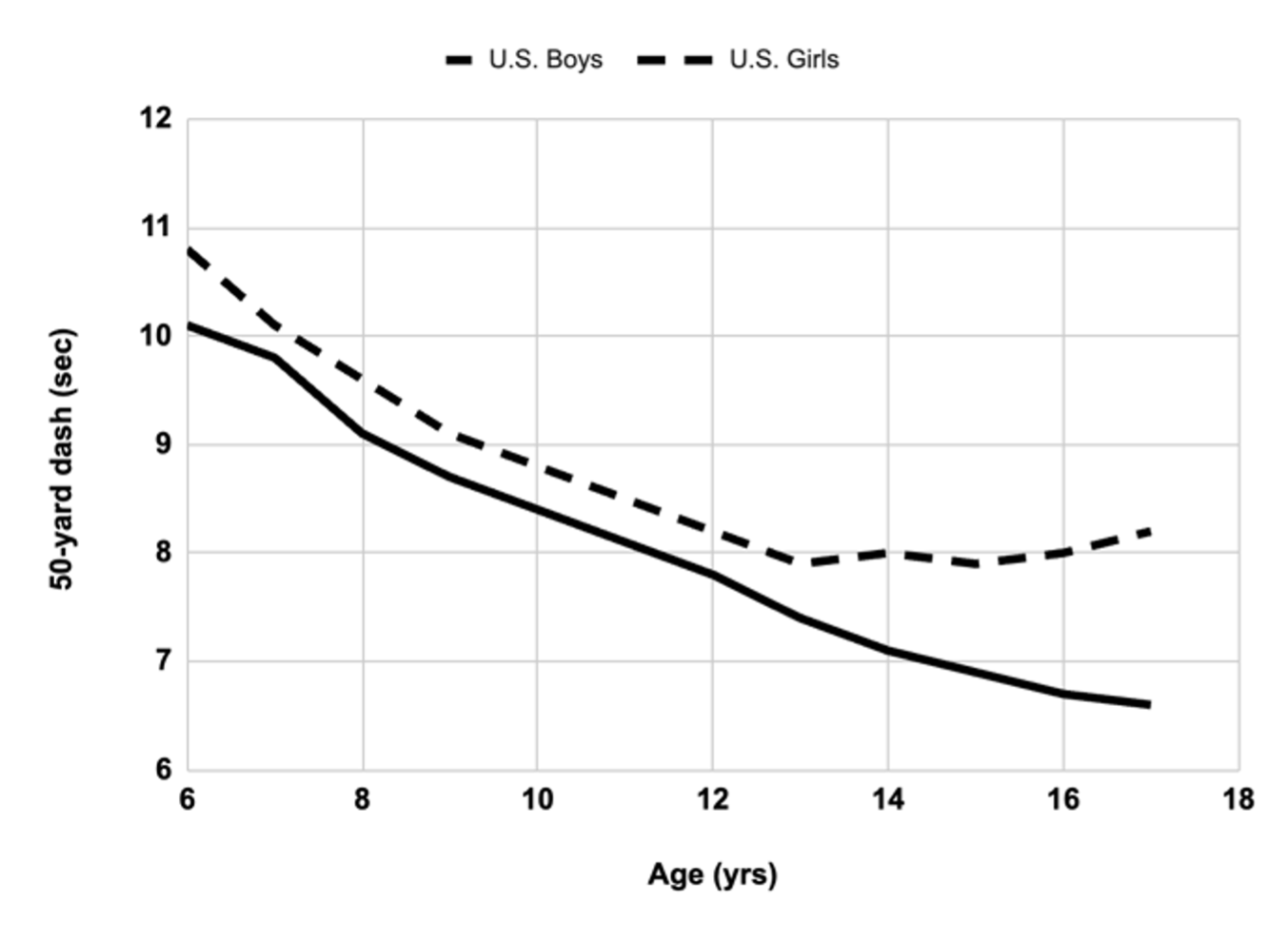

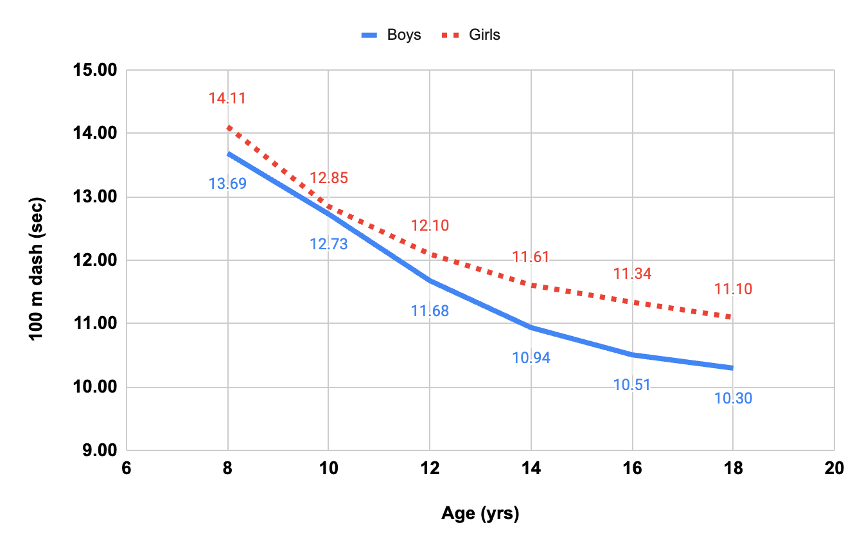

When youth fitness testing initiated in the mid-20th century, a sprint or “dash” was usually part of the testing battery; thus, there is a range of available research in the general population of youth. The graph below shows the age- and sex-associated variation in the 50th percentile of 50 yd dash performance in U.S. youth aged 6-17 yrs from the 1985 National Study of Youth Fitness. Although nearly 40 yrs ago, these data span the entire age range of childhood and adolescence unlike more recent studies of select age ranges. For comparison, I am also showing the U.S Track & Field age group records for the 100m dash.

Moving into primary or elementary school, the movement bug is still there. Invasion games like tag are a lot of fun or even just challenging a friend to a race to see who’s the fastest. As for the latter, I recall a baseball trip to the Dominican Republic where I witnessed a group of 5 boys just challenging each other to races. It was just pure, organic speed training.

There is little doubt that sprinting speed starts to become an important and coveted physical attribute in youth sports during childhood and adolescence. And related to this notion is the interest in training sprinting speed in youth.

Age-related changes in sprinting performance

As we always should – let’s “first understand the system” (see The Roots of Growth and Maturation) of the normal growth and maturation or natural development of linear sprinting speed.

When youth fitness testing initiated in the mid-20th century, a sprint or “dash” was usually part of the testing battery; thus, there is a range of available research in the general population of youth. The graph below shows the age- and sex-associated variation in the 50th percentile of 50 yd dash performance in U.S. youth aged 6-17 yrs from the 1985 National Study of Youth Fitness. Although nearly 40 yrs ago, these data span the entire age range of childhood and adolescence unlike more recent studies of select age ranges. For comparison, I am also showing the U.S Track & Field age group records for the 100m dash.